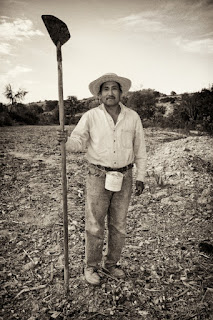

MONSANTO APPROACHES, CAMPESINOS UNITE!

April 2012

Dear Friends and Family,

The early “cajete” (ca-háy-tay)

corn, planted when the soil is still dry here in the Mixteca Alta, has sprouted

in the field below the house along with the beans and squash that accompany it

in the milpa. The technique of planting these and other companion plants

together to make up the “milpa” forms an ingeniously productive and

sustainable complex botanical community. Mutual aid, harmony, and equilibrium

hold this community of plants together and make the whole more productive than

when planted separately. And together they form a rich, shady environment in

which dozens of varieties of wild edible and medicinal plants find the unique

conditions for their own growth.

In spite of the prejudices of the occidental worldview

which proposes that without competition there is no production, in the milpa

we see that the strategy of trying to make one species compete to eliminate

all potential competitors (what is called a monoculture in modern agriculture)

is not more productive.

In spite of the prejudices of the occidental worldview

which proposes that without competition there is no production, in the milpa

we see that the strategy of trying to make one species compete to eliminate

all potential competitors (what is called a monoculture in modern agriculture)

is not more productive.

Today it is becoming evident that in

human communities as well the fierce competitiveness of the occidental vision

is, in the end, much more destructive than productive.

Last week 300 campesino men

and women from across Oaxaca met in the beautiful ethno-botanical gardens of

Oaxaca City to strategize about promoting and defending the incredibly rich

biodiversity of native corn varieties in this, the center or origin of corn.

More than 36 of the original 56-60 land races of native corn are still planted

here in the mountains of Oaxaca, along with hundreds of varieties of each race,

each adapted to the challenges of the growing conditions of its specific

region. With this incredible biodiversity and these rich genetic resistances we

hold the future of corn on the planet in our hands.

Last week 300 campesino men

and women from across Oaxaca met in the beautiful ethno-botanical gardens of

Oaxaca City to strategize about promoting and defending the incredibly rich

biodiversity of native corn varieties in this, the center or origin of corn.

More than 36 of the original 56-60 land races of native corn are still planted

here in the mountains of Oaxaca, along with hundreds of varieties of each race,

each adapted to the challenges of the growing conditions of its specific

region. With this incredible biodiversity and these rich genetic resistances we

hold the future of corn on the planet in our hands.

Yet, in addition to developing plans

to promote the planting and improvement of native seeds and to strengthen the

custom of planting in milpa in Oaxacan communities, these 300 farmers

needed also a defense plan. Under the “influence” of large international

corporations such as Monsanto, the Mexican government has authorized the very

risky business of planting genetically modified corn in this world center of

origin. The vision of competitiveness that reigns in the dominant cultures

today threatens to destroy access to the world’s sources of corn genetic

diversity through contamination and patenting of native varieties for profit.

Three hundred campesinos this day decided they will fight!

But it is dangerous to fight. Three

weeks ago Bernardo Vasquez, who worked with us on strategies for nonviolent

social change, was killed for his opposition to a Canadian gold mining operation

that is polluting the waters of his community. Two weeks before that Betina,

with whom we have also worked to develop effective strategies to protect

indigenous communal lands, was arrested on trumped up charges. Her opposition to massive private wind

farms that are taking over productive campesino lands on false pretenses, with

the cooperation of the federal government, threatened “progress”. After all, the project is hailed by

foreign environmental groups and receives UN carbon credit payments.

Privately controlled hydroelectric

projects in Oaxaca are inundating thousands of acres of indigenous lands and of

native biodiversity, against international laws that protect indigenous

territories. Indigenous communities are fighting back, while the projects

primarily designed to export electricity for private profit, ironically, receive

carbon sequestration credits.

In a recent interview well known

scientist Amory Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute suggested that the

energy needs of the Global North can easily be met by new technological

efficiencies and cheap, clean renewables in a process of conversion from fossil

fuel use led by business for profit. Neither here nor elsewhere in the Global

South do we have the luxury of such faith in the private corporation and the

innocuous character of competitive greed and business for profit.

It no doubt took many years of

careful observation and experimentation for the great, great grandparents of

the Mixtec people to understand and construct the harmonious and productive

community of the milpa. It also seems they carefully studied how to

create harmonious and productive human communities where men and women

complemented one another in producing the material, social and spiritual

necessities of everyone. Some of their wisdom has survived today in our villages’

communitarian organization, which help us produce for the common good: the tequio,

gueza, cargos, and community assemblies.

Like these indigenous ancestors, the

human family of today will have to learn how to form the complex communities of

complementarity, harmony and balanced production that we will need to overcome

the crises we face today. Neither business for profit nor governments beholden

to big money will do it.

©Phil and Kathy Dahl-Bredine, Judith Cooper Haden Photography

In spite of the prejudices of the occidental worldview

which proposes that without competition there is no production, in the milpa

we see that the strategy of trying to make one species compete to eliminate

all potential competitors (what is called a monoculture in modern agriculture)

is not more productive.

In spite of the prejudices of the occidental worldview

which proposes that without competition there is no production, in the milpa

we see that the strategy of trying to make one species compete to eliminate

all potential competitors (what is called a monoculture in modern agriculture)

is not more productive.  Last week 300 campesino men

and women from across Oaxaca met in the beautiful ethno-botanical gardens of

Oaxaca City to strategize about promoting and defending the incredibly rich

biodiversity of native corn varieties in this, the center or origin of corn.

More than 36 of the original 56-60 land races of native corn are still planted

here in the mountains of Oaxaca, along with hundreds of varieties of each race,

each adapted to the challenges of the growing conditions of its specific

region. With this incredible biodiversity and these rich genetic resistances we

hold the future of corn on the planet in our hands.

Last week 300 campesino men

and women from across Oaxaca met in the beautiful ethno-botanical gardens of

Oaxaca City to strategize about promoting and defending the incredibly rich

biodiversity of native corn varieties in this, the center or origin of corn.

More than 36 of the original 56-60 land races of native corn are still planted

here in the mountains of Oaxaca, along with hundreds of varieties of each race,

each adapted to the challenges of the growing conditions of its specific

region. With this incredible biodiversity and these rich genetic resistances we

hold the future of corn on the planet in our hands.